Introduction

There are two core motivations in sport these days: keeping athletes’ performance at peak levels and achieving better results. Sport has changed dramatically over time; it is neither pure competition nor a way of maintaining one’s physical health only. Sport has become a part of our everyday lives, as it is connected with many ties to society, politics, economy, and business. There is no doubt that sport has always belonged to the domain of culture, but today there are multicultural club teams and even multicultural national teams as a result of the self-strengthening attempts of nations as well as the effect of globalisation. This is a powerful tool which contributes to the strengthening of national identities. For instance, an American basketball player can be found in the Hungarian national team, or there are players of Turkish or Polish origin in the national football team of Germany. Professional sports teams[1] are in an ever-increasing battle for achieving the desired results, which motivates them to make use of various performance-enhancing options, such as scientific results, among many other opportunities legally available for them. This is not only about gold medals or holding the title of Olympic champion; it is more than that. Besides entertaining spectators and viewers, sport is a billion-dollar industry, a source of income for many. However, one thing should not be forgotten, the future of culture and sports culture is also at stake.

In order to enhance the performance of athletes during their training and competitions, experts rely on the most recent results in sports science research. They primarily make use of the knowledge accrued in training theory and methodology as well as physiology, disciplines belonging to the field of biomedicine. With the emergence of sport psychology as a discipline, the number of personal psychological analyses in the case of athletes and social psychological analyses in the case of sports teams[2] has grown considerably. Several excellent articles, studies, and books appeared in print discussing the factors contributing to the optimisation of performance from the perspective of individuals, partners, and teams.

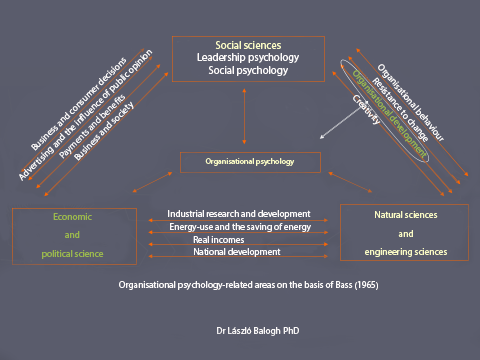

Two independent sport-related branches of science have emerged in the past 30 or 40 years, which have also justified their necessity since that time. On the one hand, various new scientific results in organisational sciences (mainly in the fields of organisational psychology and organisational behaviour studies) enable experts to identify several other performance-enhancing factors. And on the other hand, besides identifying these factors, a detailed theoretical and practical basis might be developed in order to extend the scope of performance-enhancing elements, even at organisational levels. As a matter of fact, no matter whether we take a look at individual or team sports (both categories are going to be defined later), preparation and competition take place in various organisational structures (sports club, association, etc.). Figure No. 1 illustrates the areas related to organisational psychology.

Both organisational theory and psychology have a prominent role in the field of sports management too. There has been a huge number of studies focusing on organisational culture and organisational attitudes in the international literature (see Parks, Quterman, Thibault, 2007) recently.

Figure 1: Organisational psychology-related areas by Klein (2007:369) on the basis of Bass (1965:5)

That is why it is not advisable to disregard those common problems and issues which professional sportsmen and sportswomen mention as factors influencing their performance in general: they complain that their coaches do not have trust in them, or – quite the opposite – they are thrilled as their trainers trust them completely. Many are satisfied with their positions in foreign teams while making a fortune; however, there are players who are not happy about warming the bench almost all the time despite earning loads of money abroad. It can also happen that a player inspite of taking an oath of loyalty to the club he is playing for is capable of quitting six months later to join another team, where he kisses the team’s logo on his uniform without hesitation, claiming that a childhood dream has come true with the transfer. If not getting into a national team or first team, sportsmen and sportswomen tend to feel mistreated, or sometimes they even blame club leaders for being unfair. Speaking of club leaders: guided by their intuition, they often tend to follow the principle „little money – little football, big money – big football” [as Ferenc Puskás put it, meaning that the amount of money influences how football is played], being unaware of how much damage they cause. They create problems that could be felt in the long term, not at the moment; they ruin the future of the new generation of sportswomen and sportsmen, sports culture, and athletes’ attitudes to sports. All these factors can be seen when studying the organisational culture of a sports club. What is more, when we take a look at the unwritten agreements, also known as pyschological contracts, made between employees and employers, influencing their relationships, we can also understand how these effects actually work.

It has also been widely accepted lately that psychological theories, models and laws are not present in the same way in each and every culture. What is it like, for instance, for a poor African boy to arrive in Europe at the age of eighteen after having been raised in his country of origin and having acquired the cultural values and way of thinking characterising the people of his homeland? How can a boy like this hold his ground in a culture so different from his own, where nothing could be more important than good performance? Not to mention many of those 14-year-olds who are sent to sports academies and turned into slaves in these „factories” instead of becoming successful and mentally healthy athletes. It is also interesting to see how a traineir being used to an autocratic style of leadership feels when he starts working in another culture where players have their say in questions concerning them. Thus, a conflict of roles might arise, and – regardless of the trainer’s competence – the relationship between him and the players and later their results too will be seriously affected in an adverse way. Although the question has been raised in other fields before, it might be useful to consider the same within the field of sports, namely, whether it is worth employing a trainer coming from abroad in order to have the sports culture of his own nation introduced in another culture too.

The basics of cultural sport psychology derive from the field of cultural psychology. A key concept of the former is national culture, defining it within the widest possible conceptual framework (including languages, geographical locations, religions, lifestyle, families, gender roles, openness, attitudes towards others, etc.).