Trust

The expression trust is commonly used by trainers, players, and club leaders. In situations when a trainer is made redundant, results are declining or picking up, or a player is playing a lot or little, or the same athlete is doing badly or better, problems with/the improvement of trust within the team are often mentioned.[1] Trust is a key factor in the lives of organisations, including sports teams. The members and leaders as well as the players and trainers of sports organisations and teams are in interdependent relationships; they need each other to be able to achieve good results or function in a proper way. According to Deutsch (1973), trust is an especially important factor in teams that require high levels of cooperation: members need to know whether they can trust those individuals with whom they have to work together to be able to take the risks of cooperation (Tarnai, 2003).

Does trust affect performance directly or indirectly? It is a generally accepted fact that an increase in the levels of trust within groups can improve the efficiency of group processes and members’ performance (Tarnai, 2003). However, it is not sure whether a higher level of trust is what makes performance better, or it only indirectly affects performance trough better group processes (such as changes in cooperation, decision-making, and effort put into work by employees).

The results of the research conducted by Dirk (1999) proved that a group with a high level of trust does not perform better than a group with a low level of trust, but members are motivated to make joint efforts in the former case, which might boost performance too (see Sass, 2005). In the case of sports organisations, this outcome might be especially important as group members are able to focus on the accomplishment of other goals than their personal ones. However, they might also reach their personal goals through the achievement of the shared goals of their organisations.[2] Members of a team should always maintain the feeling of being able to count on each other if needs be. The healthy functioning of a team requires mutual trust between players as well as between athletes and their trainers both on and outside the field. This is based on the assumption and expectation that ensure individuals that others will not do anything that would adversely affect those having trust in them (Tarnai, 2003). As a matter of fact, trust functions as an indicator based on previous experience reassuring members that the organisation will work in a proper way. It is by no chance that we can hear about conflicts countless times that arise between players[3], the firing of trainers proposed by a team, the loss of trust on the part of players or trainers, or crisis within the management during which leaders are unable to decide whose side they should take.

We might state that either the loss of trust or the building of trust can cost organisations dear. If we consider members’ willingness to cooperate, we can see that with a decrease in the level of trust, individuals tend to avoid situations in which they might become vulnerable or being exploited. So members seem to be reluctant to cooperate as it would be required from them in these cases (Tarnai, 2003). In addition to this, the presence of trust may also make members put more effort into their work, as they are only willing to make an effort if they feel that others also take equal part in all activities, which does not undermine their individual performance. It is an especially important factor in organisations such as sports teams where only cooperation can lead to success.

The impact of the existence of trust within sports organisations can be summarised in the following way:

- it improves team members’ willingness and abilities to cooperate, thus improving cooperation itself

- it improves the exchange of information and communication between individuals, increases the number of interactions, thus decreasing the cases when conflicts arise due to inappropriate communication, gossiping, communicational failures, and misunderstandings

- it facilitates the socialisation of new members and players, the acceptance of them, the maintenance of tolerance, thus improving organisational socialisation

- it improves group cohesion and identity

- it facilitates the work of trainers and leaders in finding solutions to professional problems (the delegation of certain tasks to players, etc.)

Does an ideal level of trust exist? Research established that either an extreme degree of trust or the lack of it might cause problems at interpersonal and organisational levels (Sass, 2005).

Should a leader put too much trust in a player, he might have a really vulnerable position as a result, not being capable of making decisions in an objective way. As we can see it, an optimal level of trust or, as Sass (2005) put it, a certain degree of „objective distrust” undoubtedly fulfils a useful function.

According to Deutsch (1973), if individuals do not believe that other members possess all the necessary abilities and motivation to work together with them in a successful way, it might alone hinder their cooperation a lot (Tarnai, 2003). In other words, should any player or member of a team or organisation have doubts about how well-prepared or committed their teammates, trainers or club leaders are, they will encounter difficulties in fitting in the team, even if they possess all the abilities and expertise necessary for perfect performance.

Shamir, Lapidot (2003) and Sass (2005) established four distinct levels of trust within organisations. (1) A general expectation of trust originates from individuals dispositional tendency to trust, while (2) interpersonal trust exists in equal and hierarchical relationships, while (3) category-based trust is typical of groups and teams, and finally (4) system trust refers to the type of trust existing related to the organisation as a whole and the impersonal structures thereof (based on roles and rules).

General trust is built on individuals’ general expectations of trust based on the patterns of their early relationships (Stack, 1983), enabling them to understand complex social situations in impersonal relationships. It refers to our trust concerning other people being on equal terms with us and the reliability of institutions and their members (Sass, 2005).

Interpersonal trust changes a lot with the passing of time spent in various relationships or with individuals’ knowledge about others in these relationships. Present conditions and future expectations related to their relationships are weighed and assessed by members on the basis of past experience.

If the emergence of interpersonal trust is limited, category-based trust will develop instead. This makes it possible for trust within a group to be established at once and speeds up the development of trust.

Finally, systemic trust refers to individuals’ belief in the reliability of an organisation or a system being comprised of various parts, which is based on the assumption that everyone fulfils the role most suitable for him within the system, as well as individuals also hold that such systems observe all the rules required for their operation.

McAllister (1985) differentiated between cognition- and affect-based trust when studying interpersonal relationships between members of organisations (Sass, 2005).

- Cognition-based trust: refers to the reliability of others, or it might also originate from the fact that individuals consider others to be competent and reliable.

- Affect-based trust: is developed during interactions with others, after placing more emotional investment into organisational relationships. Individuals might also express care and concern for the well-being of their partners, or they might contribute to the operation of an organisation by undertaking tasks voluntarily. Such results highlighted that employee relationships can be important in terms of how they impact performance (Sass, 2005).

Cognition-based trust and affect-based trust cannot be so strictly differentiated from one another in real life as the former is required for the development of the latter. In other words, in order to exhibit helpful and cooperative behaviour based on emotions in interpersonal relationships, one needs to have relationships characterised by a certain degree of trust based on expertise. This is especially important in the case of player-trainer relationships. It almost goes without saying that players decide to put their trust in their trainer when they find out about the individual’s professional preparedness (for instance, a trainer works out winning tactics for a team, or holds high-quality trainings during which players are able to feel their own development, etc.). This is something that club leaders should also bear in mind.

In hierarchical relationships, the development of interpersonal trust is affected by the fact that subordinates have limited opportunities to control the actions of their superiors, therefore when putting trust in other individuals, we might risk that they will take advantage of the situation. Placing trust in a superior depends on the person’s integrity, care, and goodwill. The feeling of risk-taking might be reduced by the perception of commitment, which is included in the psychological contract. Beccera and Huemer (2000) investigated the characteristics of trust shown by employees towards their employers. Based on their study, they concluded that the higher levels of interpersonal trust encourages more open communication with fewer emotional conflicts, and it also leads to higher risk-taking as well as faster decision-making. The main conclusion to be drawn is that trust facilitates the development of better work relationships at all levels, which might also improve performance in general.

Whitener et al. (1998) studied the risks taken by superiors when putting their trust in subordinates in hierarchical relationships (see Sass, 2005). They established that the person who puts his trust in anyone first also runs the risk that it may not be reciprocated. The competences required to fulfil their roles and the cooperation of subordinates affect the risk-taking behaviour in a positive way, whereas the possible costs incurred by someone’s taking advantage of an individual’s willingness to trust him affects the same negatively.

According to Sass (2005), “there are two key factors affecting the way interpersonal trust changes: the cognitive and emotional components of trust and the social embeddedness of relationships and systems. As a result, through obtaining information and gaining experience, the levels of trust may rise or fall.” As we can see it, trust in relationships and the levels of trust are also dynamically changing factors in the lives of organisations and their parts, which should be strengthened again and again.

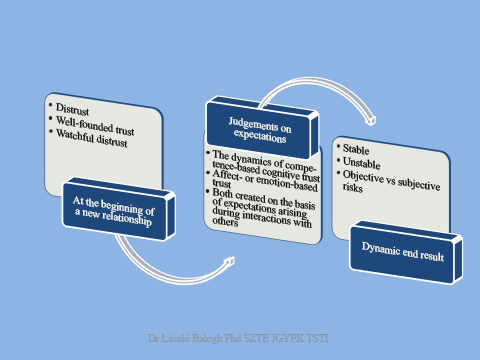

Figure 21 represents the stages of the development of trust.

Figure 21: The dynamic process of the development of trust

[1] The following sentences related to trust are taken from a Hungarian daily sport paper and are illustrative of how trust appears in communication in connection with performance: “I feel perfectly well here, and my trainer trusts me too, so I am planning to sign a contract for another two years.” “I am happy to be able to repay my trainer’s trust with scoring that goal.” “As my team’s members realised that their work pays off, they started to put trust in their joint efforts, and they were able to do anything they wanted.” “Unfortunately, due to continuous bad results, the trainer lost the trust of the managers; therefore we signed a contract terminating his employment with mutual consent on this day.”

[2] An organisation is only able to perform at its best if the personal aims of its members are the same as the goals of the organisation, or if members are capable of identifying with the goals of the organisation (Csepeli, 2004).

[3] Hans Lenk studied the behaviour of the members of Olympic men’s rowing teams and world champions and found out an interesting fact, i.e. that conflicts arising during competitions seemed to be necessary for rowers to perform at their best (Mérei, 2006:316). However, one should also note that team sports belong to the category of interactive sports where higher levels of cooperation are required than in the case of summative (additive) or coactive sports.