The development of trust

“The building of trust is a slow and continuous process, whereas the consequences of taking advantage of one’s trust might be fast and dramatic. Trust is difficult to be restored, and the willingness and conviction of both parties are needed to do so.” (Mező, 2000:30)

Trust normally becomes an issue when a new player or trainer joins a team. According to the theories on the emergence of trust, we can say that the process itself is made up of more stages, including certain presuppositions and calculative elements, being formed by several interacting factors affecting trust. We might expect that the levels of trust in newly formed interpersonal or individual-organisational relationships are rather low in most cases. However, research has proven the contrary (Tarnai, 2003): fresh relationships are characterised by higher levels of trust (or we can also see it as an attitude of “suspended distrust”[1]), which can increase or „disappear” with time. According to McKnight et al. (1996), certain elements related to organisational factors and cognitive processes may also influence the levels of trust in the beginning. The levels of trust in the beginning can be increased in the case of sports teams when individuals believe that their team is controlled appropriately and situations are dealt with similarly (which means that members assume that everything will work smoothly in their new team). A similar rise occurs in trust levels when a new member puts himself in the same category as his teammates, which means that they share the same goals and values. Zucker (1986) put special emphasis on the importance of similarities (age, qualifications, sports, club, etc.) and the feeling of mutuality (through a process or experience) in the development of trust (see Tarnai, 2003).

Research conducted by Johnson-George and Swap (1982) on the significant other and by Rempel et al. (1985) on domestic relationships also identified the same key factors mentioned above that facilitate the emergence of trust (Sass, 2005). Trust starts to develop when individuals interact for the first time on the basis of the consistency of the behaviour (predictability) exhibited by the partner. If no inconsistent information is received concerning someone’s reliability, trust continues to deepen. And as long as individuals’ experience harmonizes with their expectations, the emotional component of trust becomes of central importance, while the presence of the cognitive component may be suspended. Finally, once the relationship is set up, we have “faith in the other person”, which is manifested in the way we take care of others or return care and so on.

The degree of existing trust can also increase if one’s previous assumptions are confirmed.

Trust can also become unstable if the level of risk is high in the beginning, and expectations are not met. According to Siegel, Brockner and Tyler (1995) (see Mező, 2000), trust functions as an attributional framework that has an impact on the interpretation of anything that happens in an organisation. Trust at the same time is especially fragile, which means that if anyone takes advantage of it, one feels to be betrayed. In such cases, trust is destroyed, and distrust will take its place in the attributional framework. For that matter, transactional contracts are used to prevent such problems trough setting rules concerning anything that could be amiss so as to have an organisation which operates in a fair way. [2]

It might be interesting to see how organisations differ in terms of how much freedom certain employees can enjoy: there are cases when trust is lost easily, and there are cases when trust is maintained for a really long time.

It is also worth examining how players earn the trust of their trainers and how long trust exists between them. Whitener et al. (1998) studied the way leaders put their trust in employees and described how trust develops on the part of leaders in their theoretical framework known as Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) Theory[3]. According to them, there is an inner circle of employees with whom a leader has a closer relationship. Leaders share more administrative duties with these individuals. Furthermore, they take part in decision-making; and due to their positions, higher levels of responsibility is also given to them. At the same time, there is an outer circle of employees, who have weaker relationships with trainers, and these individuals can be considered the ones who simply perform their tasks. Much lower levels of trust characterise them then those in the previous group. Those belonging to the in-group might be more satisfied with their positions and tend to remain members of the organisation for a long time. They are also capable of performing better (with greater effort). However, leaders might risk to be exploited in the beginning in these relationships, and chances are that their trust will not be reciprocated. This model can be applied to the study of sports teams where we can find in-groups, the members of which are closer to their trainers. These individuals are typically older and more experienced players (“a council of players”), who have already earned the trust of their trainers having proved their talent. And the rest of the team members are mainly responsible for performing tasks only.

According to Sass (2015:15), systemic trust refers to “the belief shared by the members of an organisation, which is based on the interpretation of any experience that individuals have had or perceived since joining the organisation, including the positive expectations of individuals related to the reliability of the organisation that is made up of various parts as well as several cognitive and emotional elements.”

Systemic trust can be categorised in the following way on the basis of its object which might be related to three distinct aspects in the case of organisations, including sports teams too: the operation of an organisation (department, club, or team), the direct leader (trainer), and the group of employees (a group of players, a team). Trust related to the operation of an organisation is not really relevant in the case of sports organisations. Even though a sports team “uses” the emblem or the name of a club, its operation is not tightly related to that of the club; the latter might be seen as an independent department or business entity. Therefore what we should mean by an organisation in this case is a department or a team.

When examining the development of trust in sport, we should rather focus on the existence of interpersonal trust (1) between players within a team or the presence of trust between players and their trainers. What is more, I also find it important to take a look at the trust existing between players, trainers and their club (department), or, in other words, the trust related to an organisation (systemic trust) too (2). What I claim here has also been proven by the research I have conducted so far, focusing on the patterns of systemic trust in the case of sports teams.

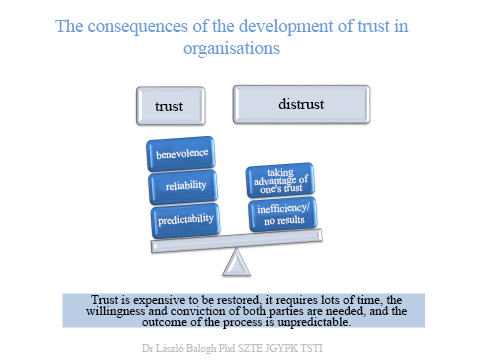

Figure 22 shows the consequences of the development of trust and distrust.

Figure 22: The consequences of the development of trust and distrust in organisations

[1] It is also worth comparing this point with the theory developed by Jones and George (1998): when relationships are fresh, the “suspension of distrust” is at work, which is followed by the stage known as conditional trust when experiencing that others have the same thoughts and feeling as we do. This generates positive feelings in individuals, who would like to maintain the relationship. Provided this condition remains, and it is not threatened by anything, unconditional trust might emerge (Sass, 2005).

[2] See also Mező (2000): A szervezeti élet igazságossága [The fairness of organisational life], PhD dissertation, Debrecen.

[3]Leader Member Exchange, in Robbins, Judge (2007): Organizational Behavior, Prentice Hall, p. 414.