Leadership behaviour

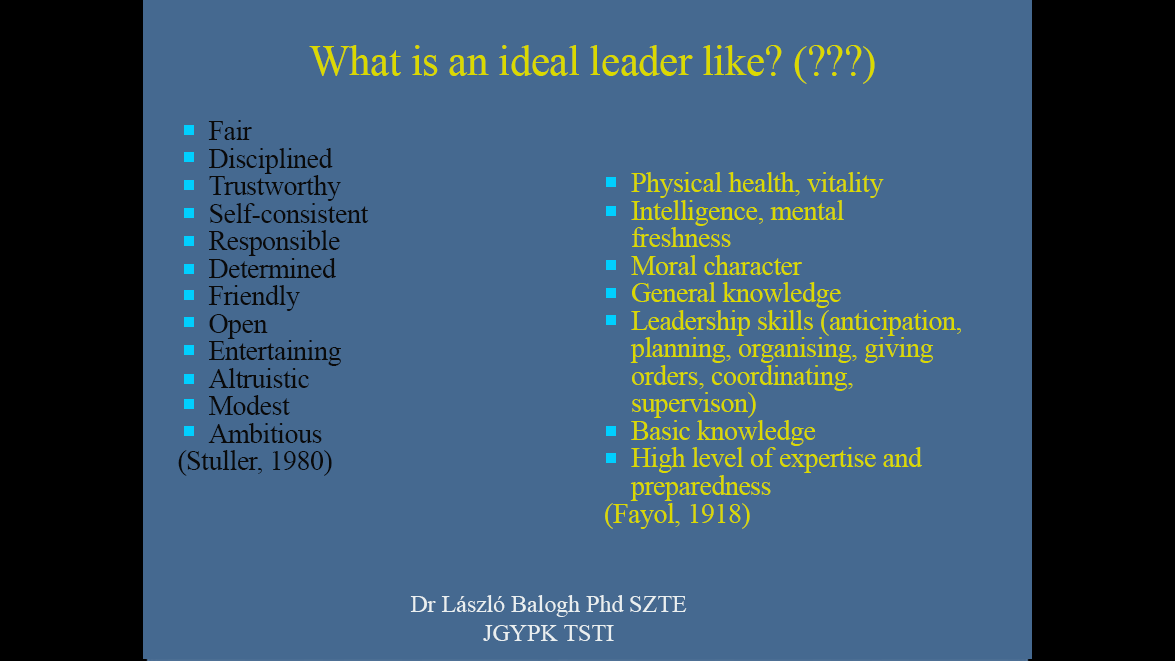

What makes a good leader? In the course of history, there have been a number of excellent leaders, great generals and statesmen making attempts to “influence”, control and monitor those being led by or subordinated to them and the way these people carried out the tasks and goals set for them. And the same is true these days. However, we have taken a long way to develop such theories like organisational theory or organisational psychology, which both claim that there is no such thing as a good or bad leader, only leaders acting in an effective and efficient way exist. Figure 14 below shows us two distinct descriptions of a good leader, which are quite interesting to study carefully as there are many decades of difference between the two.

Figure 14: What makes a good leader?

Stuller’s (1980) and Fayol’s (1918) descriptions have a lot in common despite the fact that the two scholars’ cultural backgrounds and the ages they were born in differ significantly

There have been a number of attempts to define leadership. According to Klein (2007:29), leadership may be described as a process of “achieving a goal through others’ help”. Individuals cooperate in order to reach a common goal by exploiting their abilities, energy, and talents. There is one aspect most scholars have the same opinion about, namely, it is the fact that it depends on the type of domain/environment/the “space” where leaders and those being led are present, which might be called an organisation. Figure 15 represents how the picture of a good leader has changed since the end of the 19th century in accordance with the ideological changes taking place in certain periods.

Figure 15: The evolution of the main models of leadership with special emphasis on those which are relevant to our research

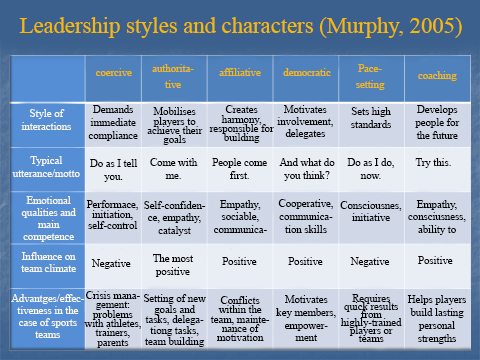

Figure 16, furthermore, provides us an interesting summary of leadership theories related to sports. The author creating the chart below considered leadership styles and characters from the perspective of sports teams; however, there are lots of common features if we think of leadership behaviours typical of sports organisations too.

Figure 16: Leadership styles in sports (Murphy, 2005)

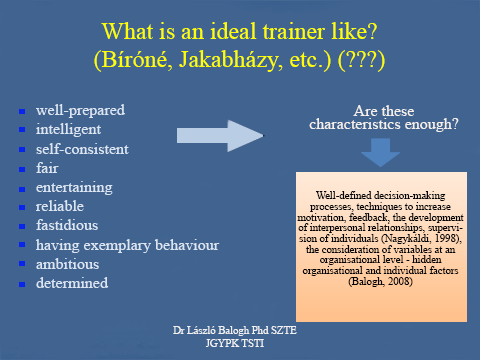

It is commonly held that the responsibilities of leaders include the following: leading and coordinating activities, setting/delegating tasks, and checking/monitoring how these processes are carried out. One might be interested in asking what makes an ideal leader. Leaders of sports organisations definitely benefit from pursuing sports themselves, enabling them to experience at first hand how such organisations work. However, being successful on the international stage as a professional athlete does not make someone a well-trained leader. The two professions differ significantly. If we try to list the names of those ex-athletes who became excellent trainers, we might not be surprised to find few examples only. Turning into a leader is a process during which one improves partly his professional competencies (however, these might develop the less, as everyone becoming a leader should have a high level of professional expertise), and mainly his personal, decision-making, communicational and other competencies. On top of this, this process takes place in a special cultural environment (no matter whether we think of organisational cultures or national cultures) surrounding the organisation. There have been many occasions when really successful trainers did not manage to do well in another country. And this cannot be explained by one’s lack of professional skills. Early classical leadership theories failed to focus on individuals’ personalities. Only later did scholars attempt to list the characteristics (including external features) of a good leader. Figure 17 summarises what is described above.

Figure 17: Is it enough for individuals to possess all the general personality traits attributed to good leaders?

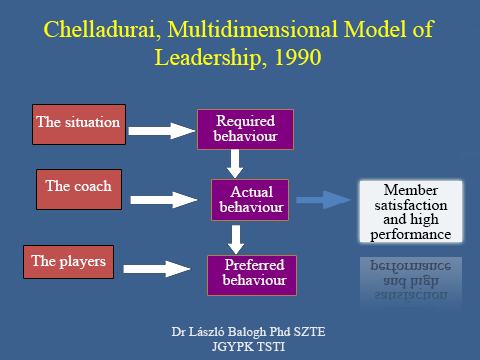

We can see that there was a need for new theories. These newly developed models typologised leaders on the basis of how they make decisions. Lewin identified the two well-known but somewhat oversimplified leadership styles: autocratic and democratic (as a matter of fact, laissez-faire is not a leadership style but an experimental situation) styles. Then there were more scholars with new typologies, for instance, Likert and Tannenbaum (see Fig. 15), who further differentiated these styles, and that is how new versions of democratic and autocratic styles were created based on how much decision-making is shared. However, scholars did not find this new approach completely applicable. Therefore, Likert et al. established a new typology of leadership styles. They took into account whether leadership activities focus around the tasks to be carried out or personal relationships. The former style is called task-oriented leadership style, while the latter is known as relationship-oriented leadership style. The same typology was embedded later into the so-called contingency model. The two theories are based on the assumption that the success of a leader mainly depends on an appropriate match between a leader’s style and the demands of the situation. There have been an attempt to developed a taxonomy for describing leadership situations (the contingency model of Fiedler), the key components of which are the leader-subordinate relationship, the type of tasks and the formal power of the leader. In this framework, leaders should find the most appropriate leadership style matching the situation, which might be a task-oriented or relationship-oriented style. It has been investigated based on a large empirical database which leadership styles may work in which situations to achieve good results. The model, in most cases, is also applicable to the study of sports organisations; however there is a need for some fine-tuning. Furthermore, a new set of theories has also emerged in sports sciences focusing on coaches’ leadership styles such as the multi-dimensional model of leadership created by Chelladurai (see Figure 18). Using the Leadership Scale for Sport, there is an opportunity for coaches to characterise themselves, as well as players can describe their coaches and the ideal coach of them on the basis of five factors (coaches’ behaviour during trainings, autocratic leadership styles, democratic leadership styles, positive feedback, social support). Then the results of the three surveys are compared (after statistical analysis) and contrasted in each category to find similarities and differences.

Figure 18: The multi-dimensional model of leadership created by Chelladurai

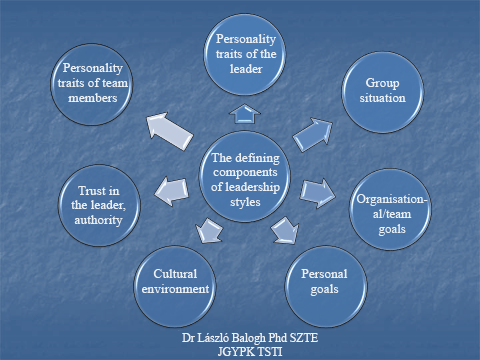

The five leadership styles described by Murphy, see Figure 16, illustrate perfectly well how early leadership theories and new approaches might be adapted to the study of sports organisations. However, it should be noted that the impact of certain leadership styles on teams mainly depends on the type of organisation. Figure 19 represents the main components of leadership.

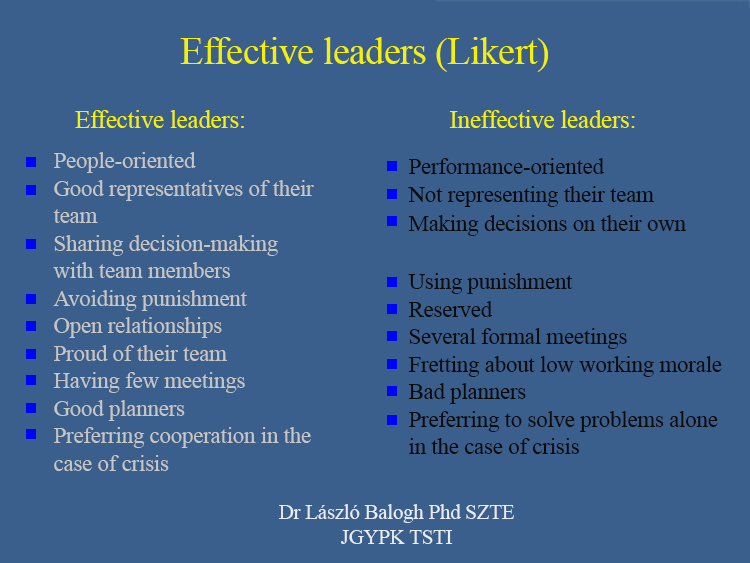

Figure 19: The defining components of leadership styles

We have referred to the notion of leadership a number of times so far without explaining what it means. Leadership is often used interchangeably with “management”. However, leadership means a lot more than management. As Bakacsi (1996:150) put it: “leadership is the ability of a leader to motivate the members of an organisation to achieve the goals set for them by their organisation.” It is also worth studying the figure below (Fig. 20) showing a comparison between the characteristics of effective and ineffective leadership styles on the basis of Likert’s description (Klein, 2007). As a matter of fact, it is crucial to differentiate between the notions of leadership and management. The former, as it has been described above, focuses on the activities of subordinates, changes, and the motivation of individuals, whereas the latter is about the coordination of an organisation, focusing on administrative tasks at an organisational level. Therefore we can deduce that being a leader or a manager differs too in terms of tasks, requiring different competences as well. Generally leadership is considered to include any possible abilities of a leader, including leadership psychological knowledge.[1] We might have seen several experts, excellent Olympic champions, or members of national sports teams who have tried their hands at being trainers or club leaders but failed in their new positions. Although these individuals are professional athletes, being able to lead a team is a distinct profession, also known as leadership, which requires completely different skills.

Figure 20: The comparison of effective and ineffective leaders on the basis of Likert’s work (Klein, 2007)